Expatriates usually make up the majority of the student body at international schools. The natural expat lifecycle plots a course in international schooling, the requirements of which can be predicted, in part, allowing international schools to develop appropriate value propositions.

Many expats are located overseas in their 30s or 40s, hence it is common for them to seek international schooling for young children. Based on our survey of new parents at international schools in the 2018-2019 academic year, 71% of parents enrolling children were for primary years, 37% for secondary, and only 8% for high school (some making enrolments at more than one stage of schooling).

But many expats start schooling children at pre-school years. For this reason, we ran a parallel survey to look at the reasons why parents choose pre-schools and compared this to the main school. We noticed that parent choices for pre-school are more basic and more consistent. For example, the choice of pre-school was predominantly their approach to learning, the reputation of the school, the appearance and upkeep of the school, and the quality of teachers.

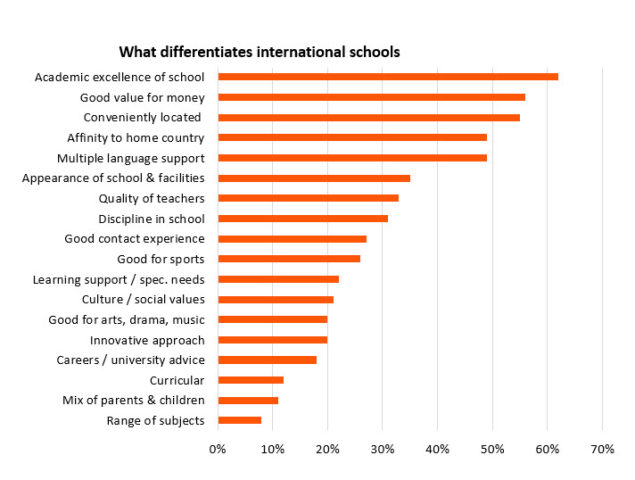

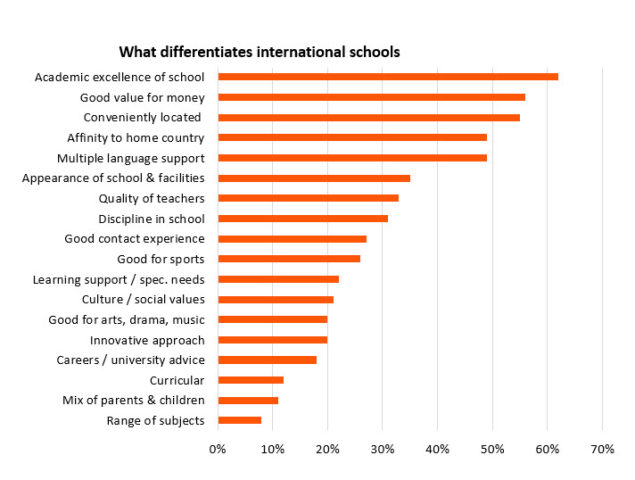

As parents move onto choosing the main school, choices start to diverge. Academic excellence can be a major driver of choice for one school, but relatively unimportant for the choice of another school. Other major differentiators of choice of international schools are the fees, the location of school, the affinity to home country, and language support (see chart below).

Generally, parents claim they will not compromise on schooling, wanting the best that money can buy, but financial pressures are having an impact on their choices. Today only 17% of parents in Singapore have school fees paid for by their employers. For this reason, some parents are choosing schools partly for their value for money, and an emerging segment of the market is the budget international school. These budget schools typically offer international curricular yet with fewer facilities, and therefore charge around only 60-70% of the fees of full service international schools. Based on our survey, nearly 30% of expat parents would consider this option for both primary and secondary schooling.

In a highly segmented market, schools can be chosen according to their ‘affinity to home country’. The diversity of international schools is universally appealing to parents, but for some they want to see a connection to their home country, which can be in the curricular but also in the culture. For long term expats, their children might have never lived in their home country. Consequently, parents can seek a school with a stronger national identity, with more teachers of their own nationality to give their children a connection to their home country.

As children progress onto middle and high schools, the parents seek schools with a wider range of subjects and better career and university counselling, although these do not serve to differentiate schools. While fewer expats enrol children for high school, as the expat population matures, high school considerations will become more important.

In high school years, some parents choose to send their children to boarding schools back in their home country. With depreciating currencies in home markets like the UK and Australia, the boarding option has become more attractive, and can be a smoother transition to university in the same country, as well as helping children develop more solid friendships. Hence, international schools see even more competition during these years.

The expat population in Singapore is changing, not only are more expats coming from more countries, but families are choosing to settle. The implications are that schools need to offer value propositions across the entire age range. We see many international schools with pre-school sections, sometimes in different locations that are more suitable to younger children, e.g. smaller, less intimidating campuses. These pre-schools act as ‘feeders’ to the main school.

But the market is further complicated by the sheer range of nationalities that schools need to serve. Clearly, this requires a level of language support, a fairly large differentiator of international schools. Many schools are developing dual language programmes, particularly to serve the new source of expats coming from within Asia itself. But culturally, international parents often want very different teaching styles, e.g. more structured, challenging (even pressured) for some, more discovery based, relaxed and expressive for others.

What is clear is that there is no one type of schooling that is suitable for every parent. It is a highly complex and highly segmented market that is always changing, and always needs researching.

Click here to read this article on BVA BDRC Asia

![[Ebook] Marketing On A Shoestring Budget](https://www.schoolhouse.agency/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/eBook-Marketing-on-a-Shoestring-Budget-1024x581.jpg)